ClimbTalk, the climbing radio show I co-hosted with Mike Brooks for nearly five years, brought a lot of Yosemite veterans into the studio. Lynn Hill, John Long, Jim Bridwell, John Bachar and Alex Honnold, to name just a few. We also had Sender Films‘ Peter Mortimer on a couple times as he was in the midst of shooting for this year’s Reel Rock offering, “Valley Uprising.” I had the pleasure of seeing this movie three times live, once as MC for the Denver premier, and I can tell you that it stands as the finest climbing film I have seen. Climbers call these sorts of things “sick.”

In honor of “Valley Uprising” premiering across the planet this year, I thought I’d offer up a tasty Yosemite morsel from a ClimbTalk interview we held a few years ago with former YOSAR ranger Dean Paschall. The piece kicks off with a little chat about City of Rocks, ID, where Dean spent a good amount of time, but hang in there. About a third of the way into the interview Dean spills the beans on the (in)famous Lodestar plane gifting the Valley with a belly full of pot. He has a unique slant on the legend, as he was there to recover bodies, blow the Lodestar to smithereens and then lift the pieces out via helicopter.

Dean also dishes on being Yosemite’s only hang gliding ranger, recoveries and rescues while working for YOSAR, watching Warren Harding drop his drawers, the history and future of BASE jumping in the Valley and some conspiracy theories about the fall-out from the Lodestar episode.

It’s a doozy… In fact, I would call it a “sick” interview. I did not fact check what he had to say, but I’ve heard all the stories before and they absolutely jived with Dean’s telling of them. Enjoy the “sickness.”

Mike Brooks: It’s 9:03 here in Boulder, Colorado and this is ClimbTalk on Radio 1190. My name is Mike Brooks. Dave McAllister is the co-host. Dave, what’s happening?

Dave McAllister: Hey, Mike. I heard you had a rough day today.

MB: I had a long work day, then I had to cover the BRC comp at the Boulder Rock Club…all well and good. And tonight on ClimbTalk we have senior management from OSMP [Open Space Mountain Parks], Dean Paschall. And, we’re expecting a call from Dave Bingham out of Idaho. I’m looking forward to that. It’s going to be a good show about Idaho sport climbing and the early days of City of Rocks. Dean, thank you for joining us.

Dean Paschall: Hey, I’m glad to be here, man.

MB: The major theme for the night, of course, is Dave Bingham, [his] climbing career in Idaho, etc. When did you first meet Dave, Dean?

DP: Dave and I first connected in the mid-70s/early-80s out in Idaho. At the time I owned a backcountry ski school and Nordic ski program out there. Dave came out from the east coast, Vermont/New Hampshire area, looking for something to do. So, I hooked him up setting track and doing a little backcountry guiding and teaching skiing. The guy is an animal – unbelievably strong. Incredible skier; one of the strongest skiers I’ve ever seen. So, [he was a] huge asset to our program out there.

DM: When he came out to Idaho, working for the ski school, was he as dedicated to rock climbing at the time or was he mostly focused on competitive skiing?

DP: He was definitely way into rock climbing but the City of Rocks was just coming on and so that was the tough thing. I mean, he had been climbing in New Hampshire, the White Mountains; a totally different sort of climbing scene. I think he’d put a fair amount of time in the Gunks. So, when you get to Idaho…it was tough. You had to sort of suss out the good climbing areas and it was pretty limited. Idaho doesn’t have the California/Yosemite style of climbing nor the east coast kind of climbing. The City of Rocks was just coming on the scene and it was sort of an interesting area. It’s just like these giant granite boulders. Two pitch, three pitch climbs, most of them. Really solid rock, but it’s obscure. It was sort of out there, so you have to make the trip.

At that point, there were not many routes, no fixed hardware or anything. It was a backcountry experience, way out a dirt road a long ways. Dave really opened the area up. We got out there and he’s like, “Oh, dude, you got to come and check this out. It’s totally untouched and amazing rock, amazing routes.” So, we started climbing out there. This is mid-70s, I guess, and it was incredible.

MB: Who found City of Rocks? Do you know, Dean?

DP: It was part of the California/Oregon Trail that was…the early explorers. So, you go out there and there’re these old carvings in the rocks and stuff from the early pioneers and wagoneers that came through there. In terms of climbing, the guy that owns the Elephant’s Perch in Idaho, in Sun Valley, Bob Rosso, was one of the early pioneers putting in routes up there. This other guy, Reid Dowdle, who is still climbing hard on the Elephant’s Perch and in the Sawtooths, was another guy who sort of opened that area. It was just a couple of local folks from the Sun Valley area that went out and started scoping it out.

DM: So, in the mid-70s, you come from California. Bingham’s coming from Vermont/New Hampshire/kind of the New York climbing scene, the Adirondacks and the Gunks, and you get to Idaho in the mid-70s. What was the climbing scene and the vibe? You know, you’re post-Vietnam, post-hippy a little bit… What are we talking about, man? Who were the climbers out there and what was that feeling like?

DP: Well, Ketchum is this full-up “sports central” area. Also, in the early-70s, it had this really loose appeal about it. It was a major ski racing area…and some uber-athletes out there and they were all sort of jonesing for a climbing area. There were some good routes in the Sawtooths but the rock, other than the Elephant’s Perch, was not really Yosemite quality rock. All of a sudden this area started becoming developed – the area around the City – and they’re like, “God, you gotta check this out.” Really good slab climbing, some good knobs, really good crystal granite like in Tuolumne Meadows, and some great crack routes, also.

All of a sudden the word started getting out… And, it was untouched. I mean, first ascents were virtually every week. Bing and I would go up there and he would put in a couple rap bolts and scope out some lines, tap in a couple of lines with chalk, on rap, put in some bolts, and we would – by lunch – have three first ascents every weekend. It was awesome. It was wide open.

MB: Would you guys toprope the routes first or would you just figure out where the bolts [went] and just run ‘em?

DP: There were very few TRs that went on. He would scope it out from the base, find the aesthetic line. Really small stuff. He put in a lot of .11s and .12s. This was early on, so they were really hard lines at that point. He would often put in the bolts and placements on rap but everything went from the ground up and it was pretty much all redpointed at that point. There was no rehearsing; no working out the moves.

DM: City of Rocks was a pretty early acceptor of bolted sport climbing, too. What was the feeling there? Was it divisive?

DP: “Acceptor” is an interesting term… That sort of suggests [an] oversight regulatory body. I mean, when you drove out there you went for miles and miles down these dirt roads and you ended up in this nice meadow area that was interspersed with all these gorgeous, lumpy boulders. There was nobody out there. There was some ranching that went on out there but there was no governmental regulatory body. It was BLM; they didn’t really care about what was happening. So, putting in a sport route or a bolted route was never considered to be anything out of the ordinary. So, putting in all these lines was what took place. It wasn’t viewed the same way that it might have been where you have a really rigid regulatory body that you might have, like in Yosemite, where the park service definitely manages that stuff pretty carefully.

DM: There wasn’t a community of trad climbers who had some push-back against that?

DP: Eh…yeah, yeah, yeah… I mean, trad wasn’t trad then because trad is what it was. That’s what you did. And don’t get me wrong – it wasn’t just bolted sport routes that went in. There was a ton of good trad climbing and the City eats up trad gear like no place. Many of the lines that originally went in were great crack climbs or utilizing some of the features. When you look at it, it just begged for some of the harder, smearier, crimpier opportunities that existed there. How are you going to do that without putting in some fixed placements?

At that point, I don’t even think it was considered sport climbing. It was like, “I want to do this line. There’s no option for natural pro here. So, I’m going to put in some placements so I can do this route.” Sport climbing almost evolved out of that. It’s sort of like when the Dawn Wall went up – the Wall of Early Morning Light – that Harding and Caldwell went up in Yosemite. That was not called “sport climbing.” They were trying to connect a couple of lines and the only way to connect those lines was bolting. So, they just put in a bucket load of bolts to be able to connect the obscure crack systems that existed there. It wasn’t sport climbing; it wasn’t trad climbing. It was what you did. It was climbing.

From that, as more and more difficult routes went up and more and more bolts routes went up and you were putting up a lot of stuff on rappel, then all of a sudden that became sport climbing. There was an evolution, but that’s not how it started out. It was just choosing the aesthetic line and you did what you did to be able to do that line.

DM: What about those first routes? I think back to Kurt Smith’s first routes and we’re talking three bolts in 115 feet. Was there an ethic there like, “Alright, we’re gonna place some bolts but there ain’t gonna be many”?

DP: There were some major runs. You definitely had to have the cajones to so some of these routes. There was sort of this ethical value that was, “Dude, this is the line. You’re gonna do it, you’re gonna take the runs.” There was [sic] no intermediate bolts placed once the line went in. Nobody came in and changed the protection that was there. There was [sic] definitely some whippers that people took as a result.

There was this one overhanging route that Dave put in that wasn’t repeated for a very, very long time. It was definitely ballsy. Very tenuous. You definitely had to consider what you were doing before you got into it. If there was an ethic there, the ethic was, “This is what I did, this is the pro we put in, this is the line that I developed and you don’t change that line.”

MB: Dean, you mentioned that you climbed with Warren Harding. Tell us about that.

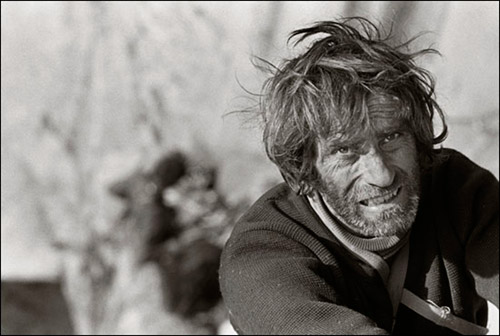

DP: Warren is a classic character. He was like the Johnny Cash of the climbing scene back in the ‘70s. I just remember being on a rescue one time when those guys were working out the line on the Dawn Wall. I think they’d been on the wall 28 days and weathered a couple of heinous snow storms and you just thought, “These guys are done; they’re dying.” So, we staged this major rescue, rapped off the top with the rangers in Yosemite and we got down to he and Dean and they were holed up in this bat hammock. No portaledges in those days; the bat hammock was just heinous. It was just some webbing strapped around some nylon. They were soaking wet, freezing cold after 20 plus days on the wall without any resupply. We thought, “These guys are done.” When we arrived there we said, “Warren, you guys need some help here?” They said, “You have a choice: You can either join us in this nice vintage of burgundy or get the hell out of here so we can finish our route.”

The guy was just a hardman, just unbelievable and pretty classic. It was unfortunate – one of my last encounters with Warren was in the Mountain Room bar. We used to call it the Mounting Room bar in Yosemite. He had gone back for, like, his 20th anniversary climb of the Nose, which he put up, as you know. He wanted to go up and reascend it and he got two or three pitches off the ground and had to retreat.

MB: How come?

DP: It had sort of gotten weathered off and, also, I think he had lost his edge. It was sort of an interesting scene. I was hanging out with Bachar, in the bar, and a few other guys. We’re like, “Warren, dude, what are you doing here? I thought you were on the wall.” And he says, “On the wall? Hell, I’ll show you on the wall!” And he dropped trou while he was standing on this table with a bottle of wine in his hand and the table fell over and he hit the deck with his pants around his ankles. We thought, “I think you’re done, Warren. Time to go.” But, yeah, he was a character…amazing guy. Warren and I did a couple of fun routes [laughs].

DM: You beat me to the punch, but I was going to ask if he lived up to his stories, his reputation. Obviously he does…

DP: No, no, no, it was a different era. There was [sic] a couple of routes that he put up…in the style that he put [them] up… Like, when he did the Nose… God, I’m trying to remember the name of the guy that would rap off almost every other day to go down and resupply and bring supplies up to these guys. I mean, they spent months on the wall trying to put this thing in.

They didn’t use a braking system to rap off of El Cap. They used the over-the-shoulder with leather pads on their shoulders and they were up and down…this guy went up and down probably every other day. They didn’t have jumars, they’d prusik back up…while Warren was up there pounding away and working out the route day after day after day, trying to figure out the King Swing and how to get through the Great Roof and the other moves. You know…months on the wall.

DM: Who is this dude? What is his incentive?

DP: You know, it was a team. These guys were tough. The stuff that’s being done now with freeing Half Dome and El Cap is unbelievable, but it was a different era and those guys were just hard as nails and persevered like you couldn’t imagine.

DM: What was it like to walk into the lodge and see Warren in there? What were the evenings like? I mean, you were a ranger down there at the time.

DP: Yeah, actually Warren showed up at my ranger station up on Glacier Point when I was a hang gliding ranger. He showed up there one time with a gallon of Yosemite Roads wine. We were doing a slide show up there with Al Bard, Tom Carter and a few other climbers. He was…he was being Warren. We were talking about the rating system, like, “Dude, I nailed this 5.9!” Warren was like, “Argh, 5.9! You youngsters don’t even know what climbing is!” He was as crotchety and gnarly as you could imagine, drinking this gallon of Yosemite Roads wine that I think he bought for a buck and a half.

He was definitely a character. He really did remind me of Johnny Cash. Just an amazing guy…

DM: Did you ever have any times where you’re a climber – you’re in the community – but you’re also a ranger…

DP: Yeah, that was a strange gig. So, I made these first flights of Half Dome and El Cap and some other features in my hang glider. I got approached and asked to be the hang gliding ranger in Yosemite. I mean, I was living in Camp 4 when they hired me to do that. In one day I’m a dirtbag hanging in Camp 4 and all of a sudden I’ve got a gun and a ticket book and this patrol car and stuff…

MB: I don’t get it. How come they just gave you a gun? I mean, one day you’re a climbing bum…

DP: Oh, that was a scary thing! Do you believe that? The first time I pulled someone over to give them a ticket I was like, “Excuse me, sir, you’re going too fast.” And this guy gets out of the car and he’s a German tourist, so he gives me his German driver’s license. I looked at my ticket book and I was like, “I don’t have a clue on what to do here.” It’s like, “Just slow down. See ya later.”

All the climbers would show up at my ranger station in Glacier Point. We had some ripping parties there. It was great. You know, I never totally abandoned my Camp 4 background. And the fact that my job was the manager for non-traditional park activities, or non-traditional sports in the national park service. I got to manage things like skateboarding through the Wawona Tunnel or base jumping off of El Cap or hang gliding in different park destinations. I had really long hair then and they liked the fact that I had this non-traditional look and I was well-connected with the Camp 4 scene and could sort of run the whole rescue operation out of there. So, I think the park service tolerated my lack of traditional park ranger-esque attitude.

DM: But they still gave you a gun.

DP: Oh, God…it was a scary thing…

DM: How did you get into hang gliding? I mean, you were the unique ranger in Yosemite at that time.

DP: That was the bizarre thing. My buddy and I built this hang glider out of visqueen and bamboo. It was in this Popular Mechanics book and I thought, “Wow, this looks intense!” And that’s why they call it hang gliding – you literally hung underneath the thing via your armpits.

I got on this thing and ran down this hill and all of a sudden it’s like, you’re running one moment and you’re flying the next. I thought, “Unbelievable…this is the coolest thing ever.” This guy, Bill Moyes in Australia, had actually towed behind a boat and had this thing called a Delta Wing. It was actually made out of aluminum and Dacron. So, I mail ordered one of these things and went out to Fort Funston in San Francisco and flew a couple of times and thought, “Wow…this thing flies!” That launched things, so to speak, for me. I started flying in Jackson, Wyoming off the ski area there and had some outrageous experiences.

And then, I thought…Yosemite. I’d climbed in Yosemite forever, lived in Camp 4 forever, and I thought, “This has got the application.” So, I went up the backside of El Cap and put this thing together and got up to the edge and I…launched off. It was an incredible flight. Dave Hitchcock, Al Bard and Tom Carter were doing a new route straight up from the Nose and I flew by those guys. They had no idea I was there. When I came by them I was like, “Dave.” He’s like, “Get out of here!” He dropped his rock hammer and totally freaked. Warner Braun was on the Salathe. So, I flew by Warner. I was like, “Warner, dude, what are you doing?” Then, went off the Diving Board on Half Dome and that was just outrageous.

And I hadn’t flown that much when I started making those flights.

DM: Who taught you?

DP: I actually sort of taught myself. I had some rough experiences off the go. I had some big crashes. I stalled a take-off one time and just bulleted straight in and hit a boulder with my hand. My hand ended up back where my elbow is and I blew my ulna and radius right out of the end of my wrist. I was actually in a cast when I opened my hang gliding school. I operated a hang gliding school for about six years right outside of Yosemite.

DM: I’m sure the students were stoked to see that…

DP: It was the cast that got me going! They were like, “Whoa, how’d you break your arm?”

“I did it hang gliding.”

“No, you do that?! Can you teach me?”

“Oh, yeah, sure.”

So, that started the whole hang gliding school.

DM: How many bones have you broken?

DP: Not that many. I’ve had some injuries, but that was probably my worst hang gliding crash, blowing my arm apart. I broke my face up and knocked out my teeth and stuff, but I learned after that. So…I haven’t broken too many bones.

DM: Do you still do it?

DP: I don’t fly hang gliders so much. A couple of years ago I went up and towed behind an ultralight in Fort Collins. But, there just aren’t that many hang gliding opportunities out here. I fly paraplanes [motorized parachute contraption] now, so I’ve got a little Beach Bonanza that we fly around and I get my flying ya-yas with that, but it’s been awhile since I’ve been hang gliding.

MB: Speaking of flying, we were talking about the dope plane that crashed in the Valley in the early/mid ‘70s and you said you had some insider information on that?

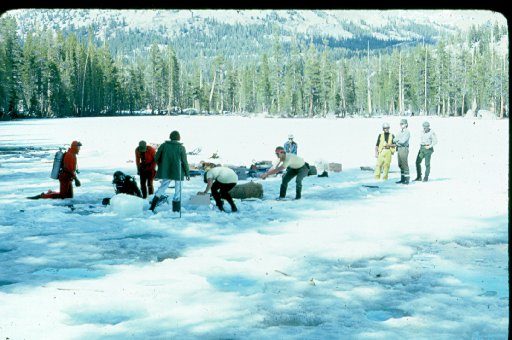

DP: So, I was hanging in Yosemite as a ranger in Glacier Point, which is the nearest ranger station to Lower Merced Pass Lake, which is where the plane went in. We got a call that somebody had found a wing up there and so we flew in to check things out and found the fuselage of this Lockheed Lodestar that was partially in this lake and partially out. On our first reconnaissance flights in we found 80 pound bails – some torn open, some still intact. They were in the lake, on the trees; there was pot hanging from the rocks and stuff. It was all over. We threw about as much as we could into the ship that we had. We went in in a Jet Ranger [Bell 206 helicopter] so we couldn’t carry too much out. We flew out and said, “Yup, some plane went in that was full of pot and we’ll go back in the spring and get it.” That was in January.

Hanging at the ranger station and all of a sudden all these characters from Camp 4 start showing up. I’m just like, “Dude, you guys cannot be doing this.” That was the launching point to head into the area. Vern Clevenger one day showed up with a mule and some chainsaws that he had borrowed from this guy, Ron Parker, who was the forester down in the Valley. He came up and he just loaded up this government mule with all this pot and hauled it out.

It was incredible, when we finally went into patrol the area it looked like a climbing store had just unloaded there. There was [sic] ice axes and sleeping bags and stuff just littering the whole area because all the guys had gone in and cleaned out all the pot from this plane. It was pretty interesting because a lot of the stuff had been soaked in the jet fuel – JP5 – that had been on this plane. When you smoked it you got this really harsh throat…

MB: How would you know about that?

DP: Well, we would, uh… It was, uh… I heard about this. I would be listening to my radio and you would hear some of these rangers going, “Ugh, erm, ergh, this is 425 calling, egh, 715…” It’s like, “Dude, I know what you’ve been doing.” It wasn’t just the climbers that made out with this.

There were guys – Chapman and a few other guys – that were just living in Camp 4, being dirtbags living in the back of their truck and all of a sudden they were going to Europe to go climbing, driving BMWs and stuff. So, out of the 8,000 pounds, the government probably recovered 1,500 pounds of it and the rest of it…

DM: Went to the climbing community?

DP: Yeah. There was an amazing event that happened out of that, though. This guy, Jack Dorn, who was one of the climbers who went in, found the flight jacket of one of the pilots.

DM: Let me stop you there for one second. Did you guys recover the pilots’ bodies?

DP: Yeah. Yeah, it was nasty. They were still in the cockpit.

DM: Was that your first time ever dealing with something like that?

DP: Oh, god no. Day one, Bridwell and I went up on this body recovery up on Cathedral Spires. I just remember the guy’s name was Robert Welcome. The guy had taken a whipper off Cathedral Spires and halfway down his boot – his foot – lodged in this crack and it just ripped his foot off. It was weeks later when we went up and found his foot. So, we had to toe tag. Usually, you toe tag the right foot. The right foot was gone so we toe tagged his left foot. You know, you put their name on there, so his name was Welcome. So, Bridwell writes on there “Welcome” and underneath it said, “To Yosemite.”

There was always this sort of morbid humor about the body recoveries we did. There was [sic] a lot of recoveries I did off Glacier Point. I would go down and do the recon on my hang glider and I’d say, “Well, there’s most of the torso…there’s the head…the remainder’s down here.” I’d sort of scope it out and find out where the guys had gone in. Then we’d go up and recover what was left.

By that time I’d done a fair amount of body recoveries.

DM: I don’t want to deviate from the story too much but we’re going to take this side track for one sec. When you become [sic] a ranger, had you ever dealt with rescues or body recovery before?

DP: No. No, that was it.

DM: So…I don’t know how to ask this. Was that traumatizing or did you steel yourself for it?

DP: It was sort of bizarre. I thought I was going to be totally freaked out by it and, you know, the rescue site in Yosemite, it was pretty amazing back in those days; Dale Bard, Al Bard, myself, Carter, Werner, all these guys. And Werner is still running the rescue site there. Bev Johnson. It was all of the people you climb with on a daily basis had a free place to stay in Camp 4. You’d stay there, pretty much, year round. When a rescue happened you’d assemble these guys because they’re the best in the Valley. That was the climbing team, the lowering team. We would often lower off El Cap on a single strand, so you’d go from top to bottom on a single strand of rope. We had this huge spool that you would lower down and go from top to bottom. It was pretty intense. It was not everybody that could do that. I did a ton of rescues out of a twin engine Huey, where they would lower us a couple hundred feet below the ship in a Stokes litter and to get close enough to the wall they would just start rocking the ship. Since you’re way below the ship you have this radical pendulum going on and when you finally hit the wall you grabbed and clipped. You were clipped into the wall with this Stokes litter, with this ship sort of hovering above you, just hoping that you don’t get any weird weather anomalies that are going to pop you off there, which did happen a fair amount. It was an interesting introduction…

The first time I got to a body, it was so bizarre. This guy that had gone off Glacier Point and I just recall he had a moustache. Everything from the moustache up was pretty much gone and the body was pretty mutilated. You look at this and you think, “Wow, I’m going to be really freaked out by this,” but it was like…dead meat.

DM: How old were you at this time?

DP: I was 20, maybe.

DM: So, you’re still immortal.

DP: Oh, yeah, totally immortal and doing crazy shit at that time. I also was in a lot of situations where people were right on the edge and probably not going to make it. So, you’re doing a lot of work on them, like CPR, where you’re pushing on their chest and hitting their backbone and trying to keep them going. You’re doing mouth-to-mouth where they’re puking blood in your mouth. The minute that they expired…there was some spark of life that just went away. They went from being this person to being just, again, some organic material. And we had to lower a lot of people in body bags down ledges and stuff; there was no alternative. It was not graceful. You were just bouncing them down. But they were gone. They were done and it was just so much organic material. By that time we were pretty accustomed to seeing dead bodies and it wasn’t horrific.

DM: Do you find that experience informed the way that you live your life or were you too young to even quantify what was happening?

DP: There was one moment where this guy, Bob Locke – unbelievable character, Bobbo – who was probably the coolest guy I’ve ever met in my life, living in Camp 4. He and Dale Bard were up on [Mt. Watkins]. Bobbo took a whipper into this corner and it was a long one. He went about 80 feet or so, hit on this corner really hard and his body hit against the rope and it chopped the rope. He dropped another hundred feet and when he hit the end he just slammed into this corner. Dale was like, “Bobbo, Bobbo, are you okay!?” This guy had major internal injuries. So, Dale rapped down to Bobbo, tied him off and said, “Dude, I got to get out of here and get some help.” He rapped off of a broken rope all the way down to the base of Mt. Watkins, had to run out of Tenaya Canyon, which is just difficult in the best of circumstances.

We had a rescue that night to try to get Bobbo out. We brought in this thing called the Carolina Candle. It was a C-140 with these huge spotlights and it literally lit up the wall. This thing just flew circles around Mt. Watkins all night. We were on top lowering Dale off on this 3000 foot spool. As we were getting closer Dale had his radio keyed open so we could talk to him. Butch Farabee was on the top with me as we were lowering them down. And that day, my very best friend in hang gliding, this guy Lee that I sort of learned to hang glide with, went in in San Francisco and got killed. So, I had just got word of Lee’s death that day, and then that night we’re lowering Dale down and as he gets down, you know, we could hear him screaming, “Bobbo! Bobbo! Dude, you okay? You okay? I’m almost there!” And all of a sudden you heard him just scream into the radio, “Butch, get me the blank out of here! Blank stinks down here!”

Bobbo had died and Dale went ballistic. Totally lost it. We had a really tough time getting him out, and so, in this moment, all of a sudden, death became real. Where before, it was getting people that [sic] fell, in this case really close friends, my two closest friends ever, died on the same day. It was horrific, and all of a sudden I just thought, “I’m going to quit. I’m going to quit flying, I’m going to quit climbing.” I wasn’t immortal anymore and it was a tough moment.

So, I approached it differently after that. I thought, I’m going to be a little smarter about it, I’m going to be a little more conscious, I’m going to be a little closer to the people that I do this with. It definitely had an impact. That was the day, the moment, the rescue that…you know, it was different. Now, it’s really personal, really close friends. That was a tough one…

DM: Well, there’s no elegant transition back to the story, but let’s go there. The pot plane. Where did we leave the story?

MB: Right before he found the black book and the gentleman’s coat…

DP: Yeah, yeah. Jack Dorn, a good friend of mine, finds this black book and a fair amount of coke, also. But, the black book, when he starts going through it, he’s like, whoa. All of a sudden he realizes there’s [sic] a lot of names and addresses that were familiar to him, that had 202 area codes. And he thought, “Oh, this is interesting.”

DM: Is 202 D.C.?

DP: Oh, it could be D.C., yeah. [It is.]

MB: Is that how far you’re going to go on that or do you want to… [laughter]

DP: And so, he made a couple of phone calls to some of the numbers in the black book and said, “Look it, we know what you’re up to. We got the whole story here. If you guys want to recover this material then it’s going to cost you.”

A couple of days later some suits showed up in Yosemite, which was interesting because it’s not an area where you see a lot of suits. They started asking about this guy, Jack Dorn. The next day, all of a sudden, the rangers get a call for this rescue up on Yosemite Point Buttress. There was [sic] a couple of guys that [sic] were two pitches down from the summit, which, you know, come one, is sort of the easiest section. And the weather was tough but it wasn’t that bad and they’re screaming for a rescue, they have hypothermia, you know, whatever. So, climbers are always hungry, they’re always willing to go up and do whatever and they felt like this was nonsense but we’ll rap down and snag these guys off there.

So, among the rescue team was a good buddy of mine, Demillis – Dennis Miller – and this other guy, Jack Dorn, and they were sort of walking in the back of the group. I was with some of the rest of the rescue team up ahead of the group and we walked up and got to the top of YPB and rapped down and you know, these guys, it’s like they seemed strangely fine for being hypothermic and screaming for a rescue and having done the hardest pitches. So, we thought, “Whatever, it all pays the same.” We hiked back down and that night we’re looking around camp and it’s like, hey, where’s Jack? Millis said, “We stopped to get a drink out of the creek and I walked away and that was the last time we saw Jack. I don’t know.” And so, he didn’t show up that night, the next day, so we thought, “Wow, that’s really weird.”

We started doing a search for Jack and we’re walking along the base of the route underneath Yosemite Falls Trail and we find Jack’s body and we’re like, what’s up with this? The official word was, well, he wore glasses and his glasses must have gotten fogged up and he walked off the cliff. You know, this guy is a hard core climber, part of the rescue team with the group and you’re on the Yosemite Falls Trail…I mean, women do this in high heels. And, you know, all of a sudden, Jack’s not there anymore and the suits then are gone. It’s just like, wow, that’s odd. It was just one of those outcomes from the pot plane that was always a bit of a mystery and never followed up on. We tried to, climbers from the Camp Four, just said, “We think you should look into this.” The rangers said, “Case closed.”

DM: Was that story widely circulated? I’m sure it was. That’s the day after the rescue, right?

DP: Obviously, everybody in camp knew that and sort of new the story and certainly had their speculations. But there was [sic] a lot of things that came out of that whole event that were…odd.

DM: Like what? If you can…

DP: I think not. It was just a strange time in Yosemite. Being at the ranger station, there was actually a classic moment where there was this guy from Tennessee that we sent in. And we would do what they call “boat patrol.” So, we had this little inflatable boat that you would paddle around the lake. This guy was in there on his own and you would have to call in for resupply. So, he said, you know, “Can you send me in two cases of ham and cheese and four loaves of bread and would you send me in one box of cookies, please?” Everybody’s hearing this on the radio, on dispatch, and the dispatcher knew exactly…this guy just had a serious case of the munchies. I mean, there was a lot of pot left up there. She goes, “I’m sorry, we didn’t get that last transmission. Could you repeat that, please?” And he goes, [in a southern accent] “Cookies. You know, them little brown things with the cream in the middle. Cookies. Could you send in some cookies, please?” And we’re just like, “Oh, dude, you are so busted.” Boat patrol was one of the favorite things that was going on in those days. It was a classic time.

I’m not sure if the statute of limitations has run out on this yet, so, you know…keep it civil.

DM: I’m sure we’re clear. So, you had to do all the paperwork for that. I’m sure you had to file a bunch of logs.

DP: No, I was just sort of a functionary within the whole system. I wasn’t responsible for filing all the reports. It was interesting. Vern Clevenger, the guy I told you about, that ripped off Charlie Parker’s mule and chainsaws and stuff. So, my buddy Ron Mackey, head of the backcountry guides, backcountry rangers at the time, stopped Vern on the way down. And Vern had this mule packed to the hilt with these bales of pot. I mean, they were just sticking out. Here he has this ripped off mule, ripped off chainsaws, you know, loaded with pot, and Ron said, “Vern, what do you got on the mule?” And Vern said, “Pot.” And he goes, “Well, I’m going to have to arrest you.” And Vern said, “Well, okay.” So, he put him in cuffs, walked him down the trail and they got down.

When the case came to court, the question was did you Mirandize this individual before you arrested him? He said, “No, it was there!” They said without advising him you cannot ask accusatory questions. So, Vern got off. It was pretty funny.

DM: It blows my mind. I’ve never heard this story so in-depth. I mean, we’ve had John Long on telling his version, we’ve had some other guys.

MB: We had Bridwell, although he didn’t touch on that.

DP: You know, Jim didn’t get as involved in it as others. It was interesting.

DM and MB: Why not?

DP: I don’t know.

DM: So, did they get the plane out of there?

DP: Yeah. We eventually went in – it was pretty classic – went in with major stacks of dynamite and blew it up into little pieces and then did sling loads out with this Llama helicopter. That was another interesting story, blowing the thing up and then flying it out.

DM: Were you there for the demolition?

DP: Oh, I got to push the plunger.

DM: No way!

DP: Yeah, yeah. Well, actually, this other guy did the first load. And the classic thing is that I’m flying in… So, we flew in with two loads and the first guy flew in with all the dynamite. I thought, I’m glad I’m not on that flight. I flew in with this box. I had this box between my legs; I had no idea.

DM: The box is the detonator, you’re talking about.

DP: Yeah. Stormin’ Norman’s flying the helicopter and I went to push the radio and he’s like, “No, no, no!” I’m like, “What?” And he’s pointing at this box of blasting caps in my lap and he said, “No radio talk, nothing. Wait until we offload these things.”

So, we flew in just bucket loads of dynamite. When we originally blew the thing out we were trying to recover some of the plane intact. So, Ron stuffed a reasonable amount of dynamite into the wings and key places and fire in the hole, push the plunger and boom. The pieces were way too big to fly out. He goes, “Forget it. This thing is not recoverable. Let’s blow it.” So, we just stuffed this thing with dynamite, everyplace. We put everything we had left in it and I go, “Ron, you know…can I do this?”

We strung a fairly long line back to this rock outcrop and I’m behind there, you know, fire in the hole, push this plunger and nothing for a minute. I thought, “Wow, something didn’t get wired.” All of a sudden there was this shudder in the ground and BUH-WHAM, this explosion that you can’t even imagine. I step out from behind the rock and it is just raining plane parts everywhere.

So, we had to pick up all these little plane parts and make these sling loads and wing it out of there. It was great.

DM: This is a Columbian operation, is how the story goes. Is that right?

DP: As far as I know. Yeah, Columbian.

DM: I think I’ve heard the story, some folks rolling into the Valley that may have had something to do with that operation. Is that right?

DP: Well…it was sort of funny because the after story was they knew when the plane… It flew into Florida and then it was doing the hop from Florida to Reno. And they had all these Feds waiting in Reno because they knew the plane was coming in. They’re waiting, waiting, waiting, and the plane never shows up and they’re like, “They evaded us somehow.” They just let it go thinking that somehow these guys had flown someplace else and landed someplace else. But, they were in bad weather, lost an engine, iced up right over the middle of the Sierras and they go in. And it was a cross country skier that [sic] was skiing out to that area – Little Merced Lake – that [sic] found the wing. When he called in the wing numbers they’re like, “We know that plane.” It was just this bizarre set of circumstances.

A couple of years after that I was hanging in the hot tub with this guy in Sun Valley and we were talking about that and he goes, “That was my load.”

DM: What?

DP: Yeah. And I’m like, “No way.” I’m sure, there was no question about the fact that was the case. It was a very strange thing.

MB: I heard that the Columbians came in shortly thereafter and wanted someone to suffer because they…

DP: Pay them back, yeah.

DM: What became of that? Is that a tall tale?

DP: Don’t know that line.

DM: I think John [Long] said something about that a couple years ago when we had him on. John Long was talking about how some shady characters came in and said, “Where are the goods? And if the goods aren’t here, where’s our money?” What are you going to get out of a bunch of dirtbag climbers, though?

DP: By that time all of the money had been sent to Switzerland and the Dolomites and other places where the Yosemite climbers all of a sudden realized whole new opportunities. And it’s amazing how quickly… I think [name withheld] did a pretty good job sequestering some of the money. Bought a place in Yosemite West and built a nice little house and stuff and got his photography business off the ground. He did a pretty good job reinvesting it. I think the others just lived the high life for a while and then it was gone.

MB: So, you say [name withheld]. Can you really say that on radio?

DP: [name withheld]?

MB: Yeah. Isn’t he…

DP: I think the statute of limitations is… And I don’t know that that’s where his funds came from. Maybe his grandmother died. I don’t know. But, all of a sudden he had a whole new lifestyle.

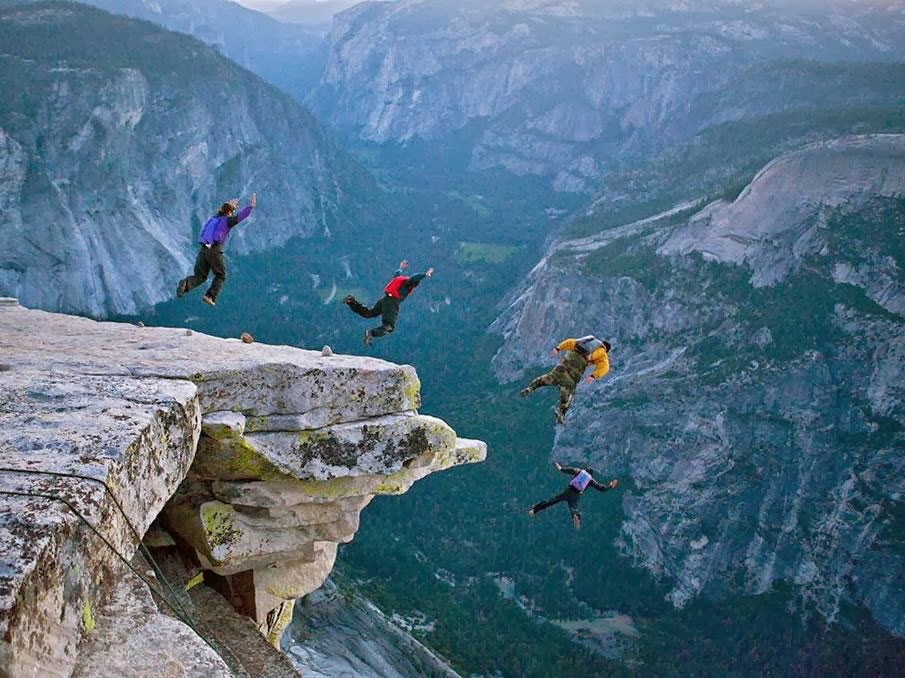

DM: We got a couple minutes left here. You were involved with the initial base jumping movement in Yosemite. Talk about that and where it stands today.

DP: In ’73/’74 there was this strange character named Rick Sylvester who did a bunch of Bond stunts after this. But he and I went up there and he jumped off El Cap with a Para-Commander, but he did it on a pair of skis. So we went up in the wintertime, built a ramp and he had these Spademan bindings and skied off El Cap with this Para-Commander chute, pulled his bindings – he had these little straps that led up his legs – and he pulled these bindings, popped his skis and then parachuted down. That was the first BASE jump off El Cap, in ‘73/’74. He did it twice. We had some wild experiences with that. And the Para-Commander chute was not the chute you wanted to jump with. He nearly wrapped back into the wall. It was nuts.

Then, in the late ‘70s/early ‘80s, BASE jumping actually started to get off the ground with Ram-Air chutes that were more directional, more efficient. So, there was a request, after we put the hang gliding program together at Glacier Point, for BASE jumping on El Cap. I sort of set up the exact same program that we had, with the same protocol, for hang gliding and it actually worked pretty well. Part of the deal was that we wanted to jump in stable air so you had to go before 8:30 in the morning; that we limited it to 10 participants per day, everybody had to have a certain rating, and that we would check everybody out before departure, before jump.

Glacier Point, it was easy to manage and regulate that. El Cap was a little more difficult and the BASE jumpers were of a little more adventurous…nature…and weren’t so keen to abide by all the regulations that we put in place. We were getting people jumping at all times of the day, people that weren’t certified to jump and on and on. At some point it just became so out of control that we said, “That’s it. We’re shutting it down.” And it was sort of a probationary period anyway that we were experimenting with this. …the hang gliding program, we had over 1300 flights there without a single incident of injury, accident or anything. It was clean. That’s not so true with the BASE jumping program. So, we decided that it probably wasn’t a viable activity. It was just too difficult to manage. So, we shut it down.

It got sort of bizarre. At the very beginning we’d literally be hanging out in the woods and waiting for these guys and they’d come and suit up and they had to show clear intent to jump. Then we’d step out of the woods and say, “Stop. You’re under arrest. That’s illegal. You’re being summonsed.” And they’d say, “Yeah, come and get me,” step off the edge and, you know, really? I mean, you think we don’t have somebody waiting for you at the base? That went on for a while and it finally just sort of tapered off. You still have a couple of renegade jumps now and then, but not like it was when we authorized it and permitted it and we had jumps there every day. It was a very cool thing.

DM: You think they’ll ever go back to a permit program for jumping?

DP: Hard to say. I mean, that was in the early ‘70s and things were a little more liberal then, a little more accepted, a little more exploratory. I think things have probably become less so, now. The tough thing is, we tried this and you guys didn’t play by the rules so we’re not going to do it anymore. It would take somebody with a really legitimate ability to go in and say, “We can manage this. We can manage the people that are doing this.” I don’t know if that’s out there.

It was way cool, though. What a place to jump. I remember my first jump off there, I was watching my feet and step, step, step, whoa… It was just like 3,416 feet of air and it was like, “This is cool.” It was so cool…

Dean’s recollection of the plane crash in Lower Merced Pass Lake is far from what went on. I have watched his video and I have to tell you either Dean is living in a dream world or he is on the edge of his later years